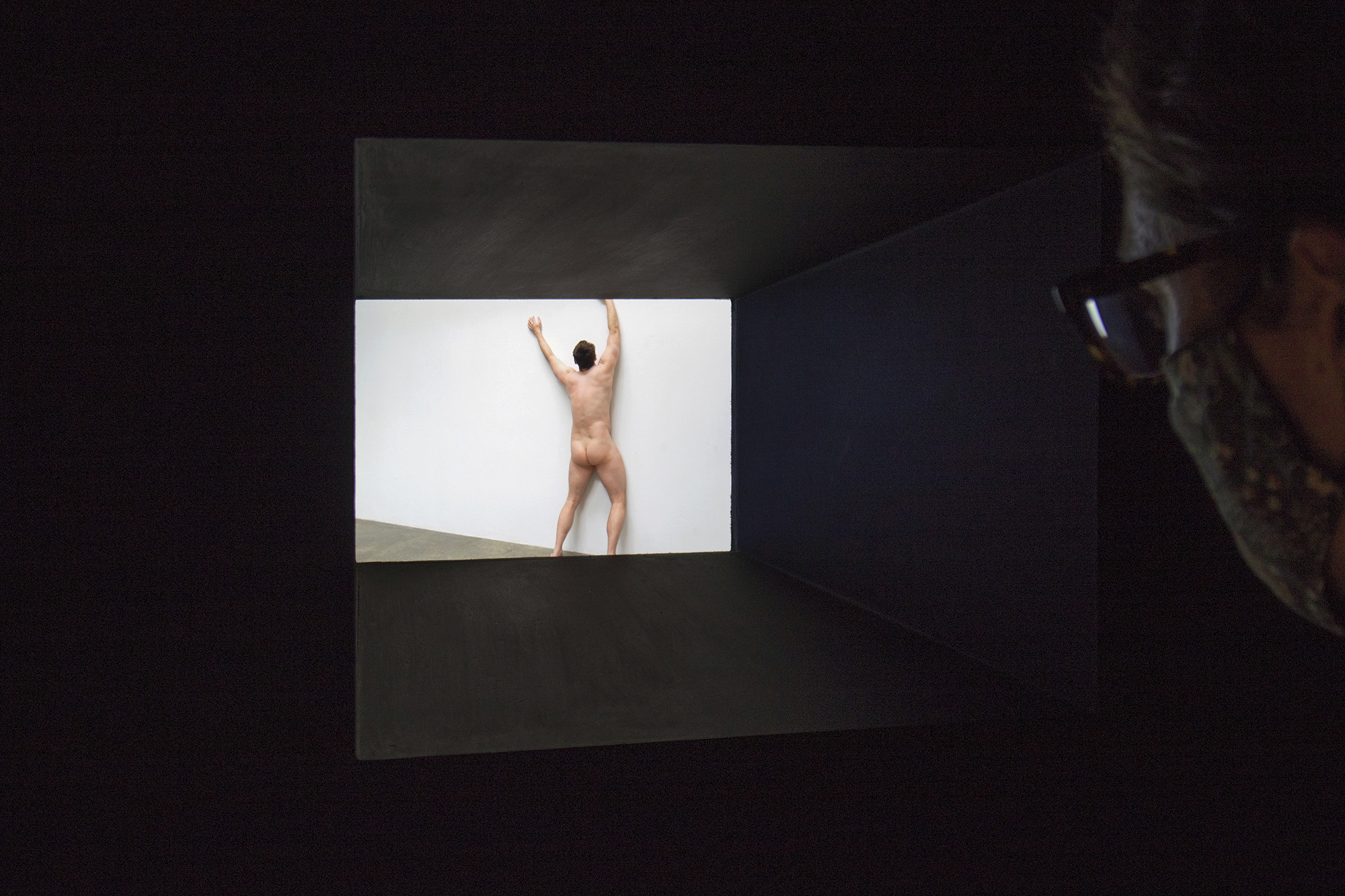

Christina A. West is an artist based in the US who makes figurative sculptures and site-sensitive installations. About two years ago she started focussing her work on the male body as a way to empower and better understand the female gaze. Her project names ‘Looking at a naked man’ and ‘She looks’ give a clear direction about what you are going to experience in her installations. I interviewed Christina about her work and the reactions it brought about.

What made you start researching the male nude?

Even with my earlier work that was mostly sculptural, I’ve always sculpted more male than female figures because I enjoy the process more—from my photography sessions with male models for shooting reference photos, to studying their form from those photos for the creation of the sculpture. Years before I created the video work, I thought that the sessions I had with my models was perhaps one of the most interesting parts of my process, though at the time no one else ever had access to that part of my work. There always is a tension during the modeling sessions that comes from a perceived power imbalance, where I am fully clothed directing the naked model as I capture their image, and that tension is complex with male models because the interaction often is tinged with a slight fear.

Why does a naked male model elicit fear?

I never am certain that the naked man in my studio won’t see the interaction as sexual or threatening and do something to harm me. So even though I do feel like I’m in control, it’s a fragile feeling that could easily be disrupted with erratic or aggressive behavior from the model. With my (early) sculpture, I would often include female and male figures together to try to set up an ambiguous narrative that conveyed some of that tension, but it always seemed like a diluted expression. And over time I got really tired of seeing so many female nudes in art and felt funny contributing to that copious archive, especially when there was such a lack of images I desired to see (of the male nude).

How did the people react to your exhibition ‘Looking at a naked man’?

During the opening reception for the exhibition, I had a few women tell me how excited they were to see images that are so rarely on view—it seemed that the gist was that it felt empowering to them to see the gaze reversed. There was a woman who attended the show, but said her husband (who also is an artist) refused to attend because of the content. I was surprised by the number of comments I heard about the model’s pubic hair—people commenting on how red it was and wondering if he dyed it. I guess this shouldn’t have been surprising since it just reveals a curiosity at seeing a part of the male body they usually don’t see in public, but it was a little disappointing for that be the most interesting part of the work for them. In social media posts various people referred to the show as amusing, disorienting, intimate, unexpected, refreshingly awkward.

Were there any interesting reactions from men?

A few months ago an artist from the UK named Andy Be sent me his response to a couple of my videos from that show. It was really great to read his thoughtful responses. About my video Discobolus, in which I filmed the duration of the model trying to hold the pose of Myron’s Discus Thrower, he had this to say:

“The model’s inability to hold the pose gave me the strength that he was lacking. By that, I mean a strength in the reality of my un-idealistic masculinity. In other words, I saw the reality of ‘self’ by noticing the reality of the model (if that makes sense). I found comfort in that. There was huge vulnerability in this work for me. I wanted to reach in, help the model in some way. Is this because I define myself as male and my masculinity depends on the model’s masculinity? Am I so polluted by patriarchal ideology that, regardless of how much I challenge ‘strength’ in my work, it is still important for me? In other words, does the reality of the model’s actual strength mess with how I want to be perceived when it comes to masculinity?”

Why do you think the male nude is still such a taboo?

I think the taboo comes from difficulty breaking the association of the penis with sexuality. Even in Classical art, where the male nude was celebrated, the penis was represented very small. They referred to small genitals as “neat” and saw the small size as representing control over one’s impulses, while Satyr’s, the sex-crazed heathens, sported large, engorged penises. So while it’s true that the male nude used be more common, the penis was always an indicator of lustful urges. I also think it’s easier for people to accept a stylized representation of the body, such as the body translated into marble or clay or paint, where the image is mediated through the artist’s imagination; there’s an implied layer of fiction to those works that makes the imagery easier for people to handle, in contrast to the stark realism of the photographic image.

Why did you specifically shift the focus to the female gaze with ‘She looks’?

It’s not so much that I shifted the focus of the work as I directed the content more explicitly with the title. I thought that the female gaze was implied in Looking at a Naked Man, since it was clear that woman was the creator of the works in the show—though in hindsight it’s hard to say how much my gender affected the read of the work. For the most part, it seemed like people were simply shocked to see so much male nudity. My next piece, She Looks, was made specifically for a group exhibition titled She is Here, so I wanted the title of that piece to play off the exhibition title while highlighting my perspective as part of the work. I don’t really think of She Looks as very different at all from the previous show. I actually think of it as a distillation of the Looking at a Naked Man exhibition into one concise piece.

How did video contribute to your research on the male nude?

I loved the directness and immediacy of working with video. Video communicates the idea of the gaze more directly because it is a less mediated presentation of my gaze. The camera is seen as a substitute for my vision, allowing the viewer to see things from my perspective. A sculpture records my vision too, but because the object is translated through so many steps, the final form doesn’t point to that as directly a lens-based medium does. I also like the way video allows for a more complex presentation of a situation or person. It can convey vulnerability alongside strength. For example, while one image, or one sculpture, could capture the body in a way that conveys graceful strength, a video of a person in that same pose will reveal their body starting to shake as muscles fatigue, or show their chest heaving as their breath becomes labored.

What projects are you working on right now?

I am still working on shooting video with male models. My most recent piece, which is still in progress, is a cheeky, updated take on Eadweard Muybridge’s high-speed photographs of humans in motion. His photos have the guise of scientific inquiry, taken in front of a gridded background, and they present a very stereotypical, cliché view of gender with sequences such as “Man Walking and Carrying a Rifle” and “Man Lifting a 75lb Boulder.” So I shot a series of actions that were more complex, like “Man Putting on Lotion,” “Man Dancing,” or “Man Eating Cereal.” And now I’m working on ways of presenting the sequences.

Did your video work on the male nude influence your sculptural work?

Yes. I want to see if I can make my sculptural work align more with ideas in the video work, so I am learning new ways of sculpting the figure that highlight my touch (and, by extension, my gaze). This means breaking my habits of sculpting with clay that I have formed over the last 15 years; my sculpted figures have always been mannequin-like, with smooth, simplified surfaces that remove all traces of my touch. But I now want my hand to be present in the work and am figuring out ways to leave fingermarks, and an overall more gestural touch, in the clay to create a more sensual form.

Check out Christina’s website and follow her on Instagram to stay updated on her work.

This interview is part of the project ‘Hij naakt zij maakt’, a project about the female gaze on the male nude.